< >

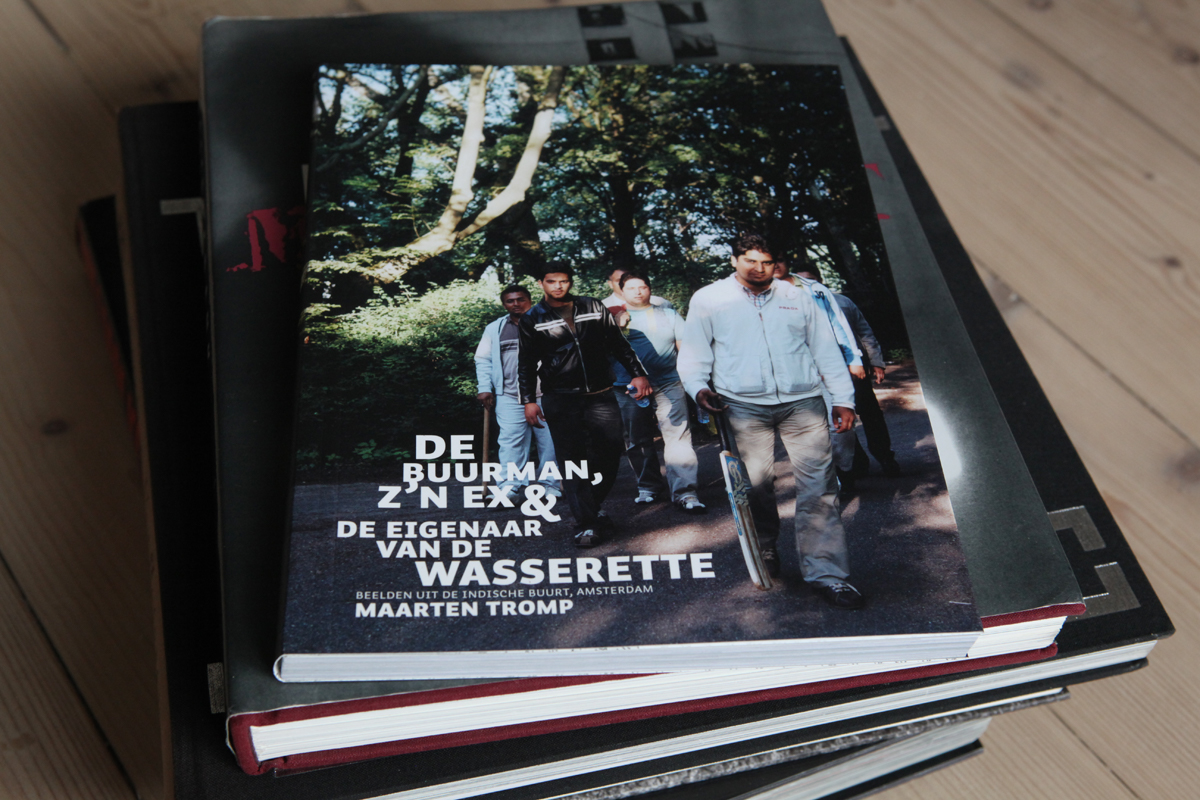

THE NEIGHBOUR, HIS EX & THE OWNER OF THE LAUNDRETTE

‘An unbearable situation escalates with death’, screams a headline in de Volkskrant one morning in september 2006. And furthermore: ‘Growing unrest in the Indische Buurt in Amsterdam after a deadly knifing. According to the residents, the neighbourhood is controlled by scum fighting over drug dealing territories’. Printed media and TV, pouring superlatives, have ethnic groups pitched against each other while competing gangs are terrorising the community. From my window I walk to the television and back. I ask myself if I am looking at the same neighbourhood that they are talking about.

For two and a half years, I have been taking photographs in the Indische Buurt in Amsterdam. With these photos, I reflect on the current, often biased formation and representation of images as in the media. I wasn’t searching for a story with a beginning and an end, but I was trying to capture the atmosphere that characterises the neighbourhood for me. A sequence of moods and emotions, alternating day and night. A neighbourhood built out of moments, places and encounters. We look and think in subconscious patterns and prejudices cloud our perception, passing what we already know - or do we?

Reviews and publications

de Volkskrant - jaaroverzicht 2008

by Arno Haijtema, 27.11.2008

‘Beelden uit de Indische Buurt, Amsterdam’, luidt de ondertitel van het fotoboek De buurman, z’n ex & de eigenaar van de wasserette waarmee de jonge fotograaf Maarten Tromp (1980) in een klap een klassieker op de wereld schopt. Met ongepolijste beelden, overdag en ’s nachts gemaakt, presenteert hij een even rauw als warm beeld van de Amsterdamse volksbuurt, waar talrijke nationaliteiten zijn vertegenwoordigd.

Na een dodelijk geweldsincident in de wijk in 2006 zag Tromp hoe de landelijke media kortstondig neerstreken in de buurt waar hij woont, voortvarend hun reportages maakten en vertrokken waren zonder zich werkelijk in de buurt te verdiepen. De naam van de Indische Buurt leek sindsdien landelijk besmet – synoniem voor multiculturele overspanning, drugsgeweld en bendevorming. Dat beeld klopte niet met de ervaringen die Tromp er heeft opgedaan.

Zijn boek kan worden beschouwd als een antwoord op de negatieve ‘pers’ en als een liefdesverklaring aan de wijkbewoners die weggestopt achter spoorwegviaducten bij de oostelijke stadsrand, het samen moeten zien te rooien. Het leven wordt er grotendeels geleefd op straat. Marokkaanse jochies, Turkse binken, Hollandse patsers, hip gesluierde en traditioneel gehoofddoekte moslima’s, orthodoxe moslims, Surinaamse evangelisten, stoere Ajax-supporters, politie, kinderen, pubers en oudjes: allemaal maken ze met grote vanzelfsprekendheid deel uit van Tromps beeldverhaal.

Het is een wervelende vertelling, waarbij Tromp in elke foto het volle leven betrapt. Iedere wijkbewoner roept emotie op: vrolijkheid, spanning, ontwapening, treurigheid. De bebouwing, de revolutiebouw uit begin vorige eeuw, de vaak uitgewoonde woonblokken uit de jaren dertig en de formica-architectuur van de jaren zeventig vormen het trieste decor, waar de bewoners met hun toko’s, wasserettes, nailshops en telecomwinkeltjes toch weer uitbundig kleur aan verlenen.

Tromp is niet naïef. Er hangt een zekere spanning in de wijk, en ook die maakt hij zichtbaar. Bloemen bij een plaats delict, jongens met enge honden in het park, duistere straten waar je liever niet komt. Juist de manier waarop hij het gevoel van ongerustheid combineert met het poëtische straatleven maakt zijn boek tot een monumentaal document van het grotestadsleven aan het begin van de 21ste eeuw.

Tromp treedt in de voetsporen van Ed van der Elsken.

Arno Haijtema in De Volkskrant, bijlage 'Horen en Zien 2008' 27.11.2008

Tijdschrift Rosa

by Erik Schumacher, 09.10.2008

In september 2006 trekt een dodelijke steekpartij met rumoerige nasleep in de Indische Buurt in Amsterdam landelijke aandacht. De negatieve berichtgeving over de buurt bereikt een hoogtepunt, en kranten en televisieprogramma's buitelen over elkaar heen met het ene alarmerende verhaal na het andere. In de Indische Buurt staan verschillende bevolkingsgroepen lijnrecht tegenover elkaar, klinkt het, en maken rivaliserende bendes de straten onveilig. De buurt staat, kort gezegd, op ontploffen.

Buurtbewoner en fotograaf Maarten Tromp loopt heen en weer tussen zijn televisie en het raam. Woont hij echt in dezelfde buurt als waar op televisie over gesproken wordt? Natuurlijk, de sfeer in de Indische Buurt is anders dan in de gemiddelde Vinex-wijk. Zo'n zestig procent van de inwoners is van niet-westerse afkomst. De bevolking is relatief jong en laagopgeleid. Nergens in de stad is het percentage lage inkomens zo hoog als in het westelijke deel van de buurt. Maar het is in de Indische Buurt ook veiliger dan gemiddeld in Amsterdam. Tromp ervaart de buurt door haar afgezonderde ligging achter het spoor bovendien als een oase van rust in de gejaagde stad. Een buurt met een eigen karakter, dorps en grootstedelijk tegelijk. De Indische Buurt die hij kent, is een heel andere dan die hij op televisie ziet.

Tromp is op dat moment al bezig met een fotoproject over zijn buurt, mede in reactie op de beeldvorming in de media en de politiek. Het mediaspektakel rond de steekpartij sterkt hem in de overtuiging dat dit belangrijk werk is. Nu, twee jaar later, ligt zijn boek in de winkels: De buurman, z'n ex en de eigenaar van de wasserette.

Eenzijdig en veelal negatief, zo noemt Tromp het beeld dat de media schetsen. 'Enerzijds is het de bekende hang naar sensatie: goed nieuws is geen nieuws en slecht nieuws verkoopt. Anderzijds is het ook luiheid en gemakzucht. Het is veel makkelijker om in hetzelfde straatje te blijven hangen dan om een keer een stap verder te gaan en om de hoek te kijken.'

De invloed van de beelden uit de media moet volgens Tromp niet onderschat worden. Ze beïnvloeden wat mensen zien als ze over straat lopen, en dat zit hem ook in de kleine, onopvallende dingen. 'Als er op het NOS-journaal bijvoorbeeld een item is over de hoge werkloosheid onder allochtonen, krijg je daar standaard beelden bij te zien van een markt in Amsterdam of Rotterdam met Turkse of Marokkaanse vrouwen in lange jurken, die anoniem en schichtig voorbij schuifelen. Iedere keer wordt er uit dezelfde doos archiefmateriaal zo'n fragment gehaald. Op het moment dat je zelf over zo'n markt loopt, krijg je daardoor automatisch de associatie met die negatieve berichten over die allochtonen die er na vijftig jaar nog steeds niets van bakken.'

Met zijn boek wil Tromp de strijd aangaan met de beeldvorming in de media en mensen met hun gekleurde blik confronteren. Zijn foto's tonen in een eerste oogopslag vaak de bekende beelden van straatcultuur in arbeiderswijken, maar verraden bij nadere beschouwing de nuances die daarachter schuilgaan. Bij een eerste blik op het omslag van het boek zien we een groep Hindoestaanse jongens dreigend op ons aflopen. Zijn dat knuppels in hun handen? Nee, het zijn cricketbats. De jongens lopen terug van een wedstrijdje in het park. Op een andere foto poseren drie jonge Marokkanen in hiphopkleding stoer voor de camera. Ze lijken zich heel wat voor te stellen van het plaatje, maar zien niet dat een bejaarde vrouw op de achtergrond geamuseerd toekijkt.

'Ik vind het leuk om te werken met de suggestie,' zegt Tromp. 'Je reikt iets aan in een foto, en vertelt maar een deel van het verhaal. Een foto roept vragen op en laat tegelijkertijd de ruimte open voor je eigen invulling. Hierdoor ben je genoodzaakt je eigen verhaal te creëren, waarbij je vroeg of laat altijd je vooroordelen tegenkomt.'

Steeds was Tromp op zoek naar intieme beelden, en die leverden de beste foto's op. Opvallende en onopvallende buurtbewoners laten iets van zichzelf zien, waardoor we na één foto al het gevoel hebben ze een beetje te kennen. 'Door naar individuele karakters te kijken,' stelt Tromp, 'kom je los van je bevooroordeelde blik. Iedereen heeft een bijzonder karakter, maar je moet het wel kunnen en willen zien. Een gevoel van onveiligheid hangt vaak samen met de angst voor het onbekende, en dat is uiteindelijk een van de dingen waar dit boek over gaat: de identificatie met iemand waar je normaal gesproken niet naar om zou kijken of zelfs met een grote boog omheen zou lopen.'

In alles ademt het boek een liefde voor de volksbuurt, waar de rafelrandjes van het stadsleven ontbloot liggen in een sfeer van opgewekte soberheid. Tromp ziet ook nadrukkelijk schoonheid in de duistere kanten van de buurt: een aanzienlijk deel van de foto's maakte hij 's nachts. Vaak missen die nachtfoto's een duidelijk onderwerp. Het zijn composities van schimmen. De straten zijn leeg, en de nachtwandelaars verzamelen zich in kleine groepjes. Het is vaak onduidelijk waar ze mee bezig zijn, en dat schept een suggestie van avontuur. Voor Tromp waren de onvoorspelbare situaties waarin hij tijdens zijn nachtelijke tochten belandde vaak even belangrijk als de foto's waarmee hij thuiskwam.

'De commercie en het vermaak van het 'hippe' Amsterdam lijken ver weg,' schrijft hij tevreden in zijn inleiding. Maar op een foto van een graafmachine die het puin van een gesloopt huizenblok verzamelt, werpt de ontembare zucht naar vooruitgang haar schaduw al vooruit.

Er is geen buurt in Amsterdam waar sociale huurwoningen in zo'n rap tempo verdwijnen als in de Indische Buurt. Drie grote woningcorporaties hebben de handen ineengeslagen om de buurt 'op te knappen'. Samen investeren ze 275 miljoen euro in het 'Wijkactieplan', dat bijvoorbeeld van de Javastraat, de belangrijkste slagader van de buurt, een 'Mediterraanse winkelboulevard' wil maken. De corporaties doen dit uiteraard allesbehalve belangeloos: in ruil voor hun investering mogen ze 2200 sociale huurwoningen opwaarderen of verkopen. Het stadsdeelbestuur toont zich in het kader van de ambitie om 'aan te sluiten bij de stedelijke dynamiek' in het wijkactieplan dolenthousiast over de verwachte toestroom van de middenklasse.

Voorlopig is Tromp niet bang dat zijn buurt, in navolging van voormalige volksbuurten De Pijp en de Jordaan, door een vloedgolf van yuppen haar oude karakter zal verliezen: daarvoor is het aantal sociale huurwoningen in de Indische Buurt vooralsnog te groot. Toch is plaatst hij kanttekeningen bij de stadsvernieuwing, die ook op andere Amsterdamse buurten, zoals De Baarsjes, Westerpark, Noord en het Wallengebied, haar stempel drukt.

'Wat mij met name stoort is de manier waarop er over gesproken wordt. De oude buurt wordt weggezet als een achterstandsbuurt waar het slecht gaat, en de middenklasse wordt gepresenteerd als het wondermiddel dat alle problemen op gaat lossen. Ik heb op zich niets tegen het mengen van verschillende inkomensgroepen, en ik ben helemaal niet tegen de middenklasse. Als ik wat meer verdien ben ik zelf ook lid van de middenklasse. Je kan de middenklasse ook niet over één kam scheren. Maar vaak zie je dat het totaal niet mengt als je de middenklasse naar een arbeiderswijk haalt. Het komt zo'n wijk niet per se ten goede, omdat het gescheiden werelden blijven.'

'Je krijgt in de Jordaan mensen die klagen over het luiden van de Westerkerk. Dat moest maar eens afgelopen zijn, terwijl het een eeuwenoude traditie is. Ik zag op televisie een programma over een oude wijk in Noord, die grondig vernieuwd gaat worden. 'Het is toch eigenlijk niets hier,' zeiden ze, 'er is niets te doen.' Dan denk ik: voor wie is er niets te doen? Ja, voor de nieuwe middenklasse is er niets te doen, want er zijn geen hippe cafés en culturele aangelegenheden. Maar de mensen die er nu wonen zijn misschien wel heel tevreden.'

De kolonisatie van arbeidersbuurten door de middenklasse leidt volgens Tromp bovendien tot vervlakking en eenheidsworst. 'Alle plooien worden rechtgetrokken, terwijl juist die plooien de stad maken en voor haar karakter zorgen.'

Tromp heeft dan ook weinig op met het politieke adagium dat buurten met veel lage inkomens 'gered' kunnen worden door de middenklasse binnen te halen. 'Het beleid impliceert dat het welzijn en geluk van mensen afhankelijk is van het kapitaal in hun buurt. Maar welzijn heeft natuurlijk met veel meer dingen te maken dan met welvaart. Dat is een andere belangrijke boodschap van mijn boek: kijk eerst goed naar wat er is en wat je hebt, voordat je het allemaal om gaat gooien.'

Erik Schumacher in Tijdschrift Rosa 09.10.2008

Credits Magazine / Talent

by Fabian Takx, 01.2009

Het Parool 'Kleurrijk, nog niet trendy'

by Corrie Verkerk, 16.08.2008

Radio interview VPRO de Avonden

by Gijsbert van der Wal, 30 min, 05.11.2008

NRC Handelsblad

by Karel Berkhout, 05.09.2008